Understanding Materiality and Scope in Sustainability Reporting

In today's business landscape, sustainability reporting has become more than just a trend; it’s a critical component of corporate strategy. Companies are increasingly held accountable not only for their financial performance but also for their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) impacts. As stakeholders demand greater transparency, understanding the concepts of materiality and scope in sustainability reporting becomes essential for organizations aiming to deliver meaningful and actionable insights.

Crafting a compelling and impactful sustainability report

requires careful consideration of two key concepts: materiality and scope.

These concepts are crucial for ensuring that sustainability disclosures are

relevant, focused, and meaningful to stakeholders.

In this blog post, we will explore these concepts in depth,

offering practical guidance on how to assess materiality and define the scope

of your sustainability reporting to ensure it resonates with your audience and

aligns with your business objectives.

Materiality: Prioritizing What Matters Most

It essentially asks, "What matters most to our

stakeholders?" Identifying material issues helps organizations prioritize

their sustainability disclosures and focus on the aspects that are most

relevant and impactful.

For example, a manufacturing company might find that

reducing carbon emissions is material not only because it lowers operational

costs but also because it meets regulatory requirements and aligns with

stakeholder expectations for environmental responsibility. In contrast, a

service-based company might prioritize data privacy and employee well-being as

material issues, reflecting their operational focus and stakeholder concerns.

There are different types of materiality:

Financial Materiality: This relates to the

potential impact of sustainability issues on an organization's financial

performance, such as costs associated with environmental regulations or risks

related to climate change.

- Climate

Change: A company operating in a region prone to extreme weather

events might report on the financial risks associated with climate change,

such as potential damage to infrastructure, supply chain disruptions, and

insurance costs.

- Water

Scarcity: A beverage company operating in a water-scarce region

might report on the financial risks associated with water scarcity, such

as increased water costs, potential production disruptions, and

reputational damage.

- Energy

Costs: A manufacturing company with high energy consumption might

report on the financial impact of energy costs, including the potential

for price fluctuations and the need for energy efficiency initiatives.

- Regulatory

Compliance: A company operating in a sector with stringent

environmental regulations might report on the financial costs associated

with compliance, such as fines for non-compliance and investments in

pollution control technology.

Social Materiality: This focuses on the social

implications of an organization's actions, including labor practices, human

rights, and community relations.

- Labor

Practices: A company with a global supply chain might report on

its labor practices, including fair wages, working conditions, and

employee safety.

- Human

Rights: A company operating in a region with human rights

concerns might report on its efforts to promote human rights within its

operations and supply chain.

- Community

Engagement: A company with a significant presence in a local

community might report on its community engagement activities, such as

supporting local initiatives, providing employment opportunities, and

promoting social responsibility.

- Diversity and Inclusion: A company committed to diversity and inclusion might report on its efforts to create a diverse and inclusive workplace, including representation of different genders, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

Environmental Materiality: This encompasses the

environmental impact of an organization's operations, such as greenhouse gas

emissions, water usage, and waste management.

- Greenhouse

Gas Emissions: A company with a large carbon footprint might

report on its greenhouse gas emissions, including the sources of

emissions, reduction targets, and progress towards achieving those

targets.

- Waste

Management: A company with significant waste generation might

report on its waste management practices, including waste reduction,

recycling, and disposal methods.

- Water

Usage: A company with high water consumption might report on its

water usage, including water conservation efforts, water quality

management, and water footprint reduction.

- Biodiversity Conservation: A company operating in a region with high biodiversity might report on its efforts to conserve biodiversity, such as habitat restoration, species protection, and sustainable land management.

These examples illustrate how materiality can be applied

across different industries and sectors, highlighting the specific

sustainability issues that are most relevant to an organization's financial

performance, social impact, and environmental footprint. By focusing on

material issues, sustainability reports become more meaningful and impactful

for stakeholders.

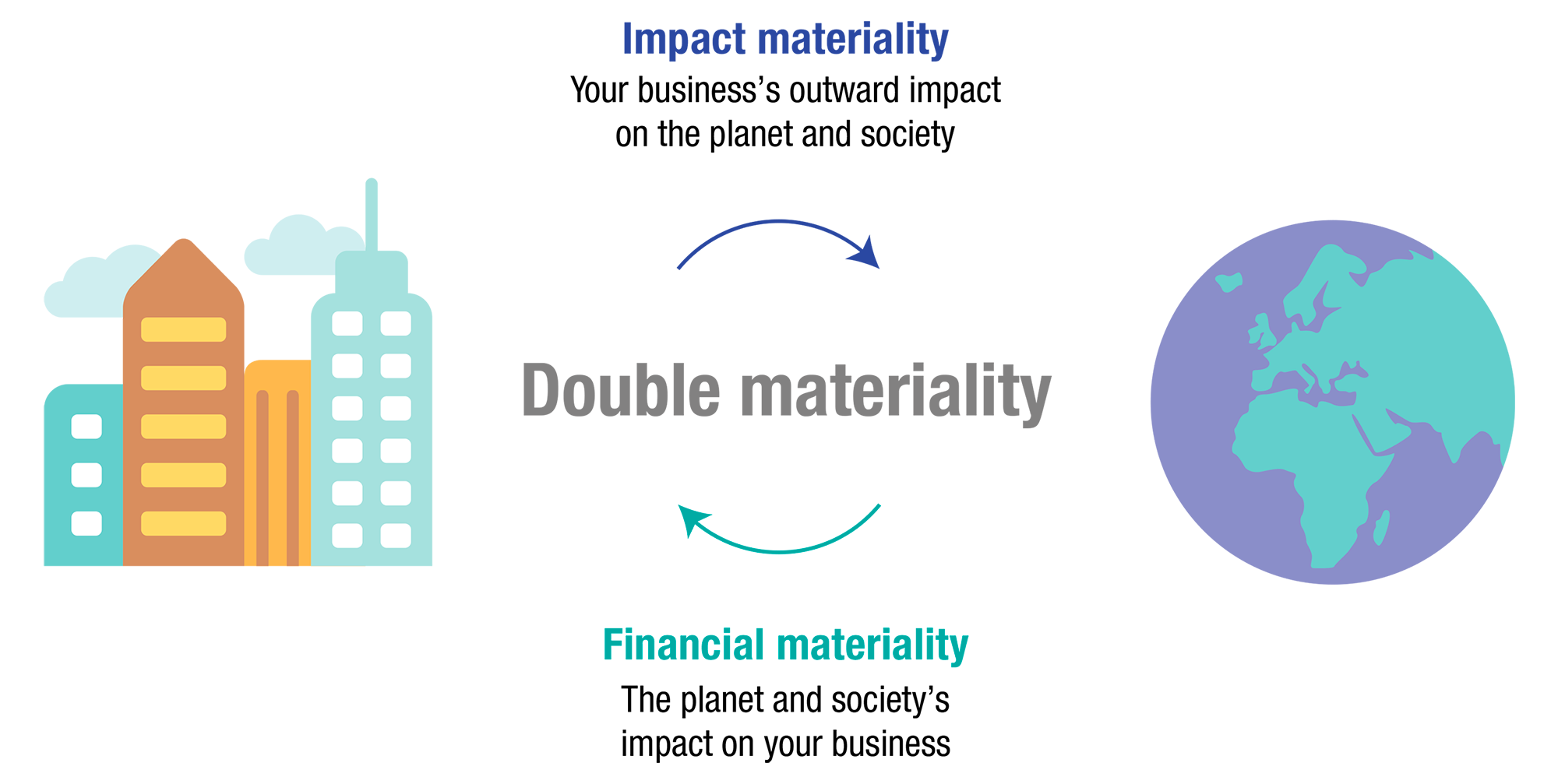

Double

Materiality Explained

The Concept of Double Materiality

Double materiality extends the traditional accounting

principle of materiality beyond financial considerations to include

environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors. It recognizes that

sustainability issues not only impact a company's financial performance but

also affect the environment, society, and broader stakeholders. Double

materiality acknowledges the interconnectedness between a company's operations

and activities and their broader impacts on the world around them.

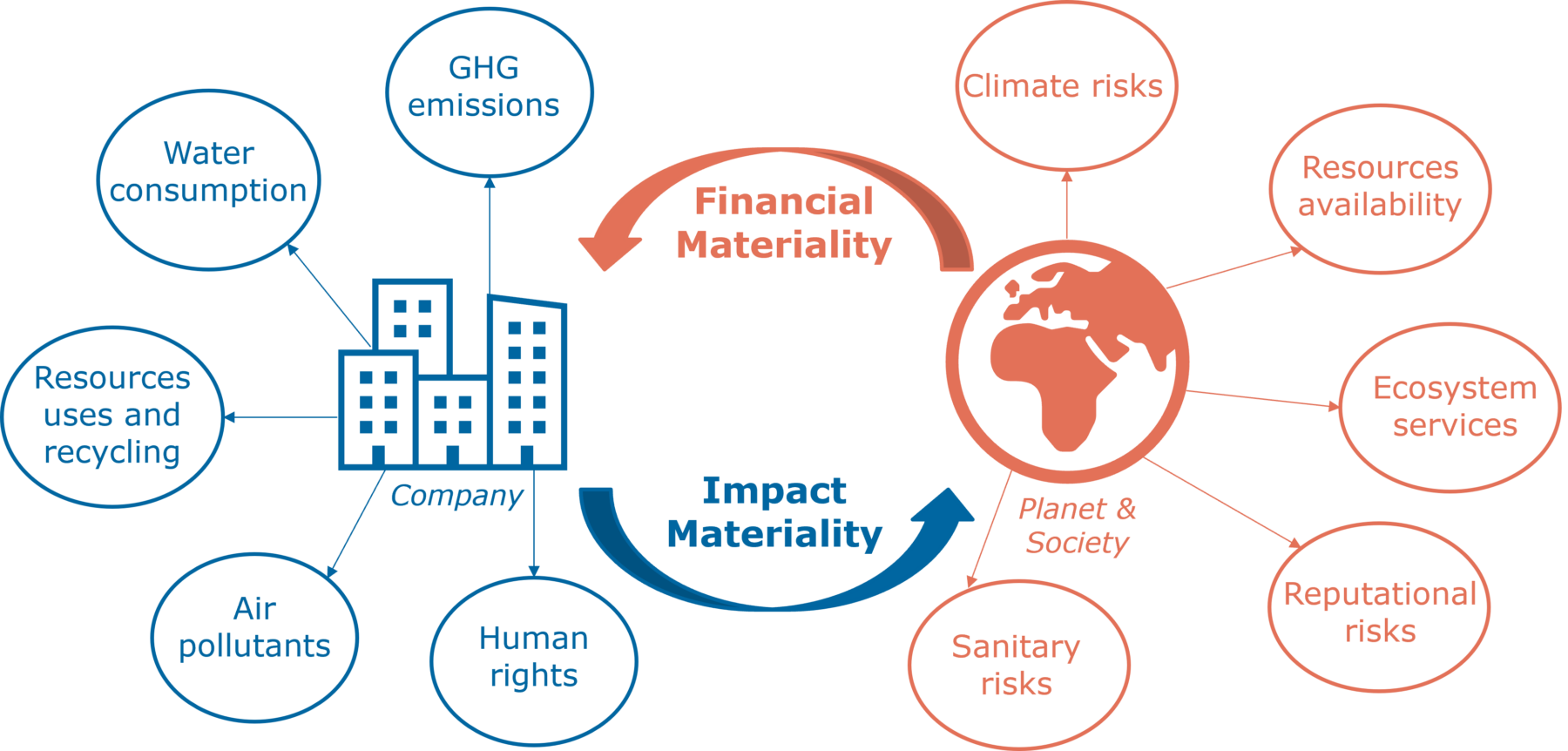

Double materiality refers to the recognition that sustainability issues can be material in two distinct but interconnected ways:

Financial Materiality:

This aspect of materiality focuses on how sustainability

issues impact the company’s financial performance, value, and long-term

viability. For example, climate change could be financially material to a

company if it leads to increased costs, regulatory penalties, or shifts in

market demand that affect profitability. This is the traditional view of

materiality, which is primarily concerned with the implications of

environmental, social, and governance factors on the financial health of the

company.

Impact Materiality:

Impact materiality considers how the company’s operations,

products, and services affect the environment, society, and broader economy.

This perspective looks at the external impacts that a company’s activities have

on stakeholders, including communities, employees, consumers, and the natural

environment. For example, a company’s carbon emissions or labor practices may

be considered materially significant because of their broader societal or

environmental impacts, even if they do not have an immediate financial effect

on the company.

Importance of Double Materiality

Double materiality is important because it broadens the

scope of what is considered "material" in sustainability reporting.

It encourages companies to disclose not only the financial risks and

opportunities related to sustainability issues but also the societal and

environmental impacts of their actions.

This dual perspective is particularly relevant in the

context of increasing regulatory requirements and stakeholder expectations.

Investors, regulators, consumers, and other stakeholders are increasingly

demanding transparency not just about financial risks, but also about the

broader impacts of corporate activities on the world. Double materiality

ensures that these concerns are addressed in sustainability reports.

Application of Double Materiality

- Sustainability Reporting: Companies integrate double materiality principles into their sustainability reports to disclose how sustainability issues affect their business and how their operations impact the environment and society. Global reporting standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) incorporate double materiality concepts into their reporting frameworks.

- Corporate Strategy: Companies use double materiality assessments to align their sustainability initiatives with their corporate strategy, ensuring that sustainability is embedded in their business decision-making.

Benefits of Double Materiality

- Enhanced Transparency: Provides a more comprehensive view of a company's sustainability performance and impact.

- Improved Risk Management: Helps companies identify and address sustainability risks and opportunities more effectively.

- Stakeholder Trust: Demonstrates a company's commitment to transparency, accountability, and responsible business practices.

Double materiality is a vital concept in sustainability

reporting that recognizes the interconnectedness between financial performance

and broader ESG impacts. By integrating double materiality principles into

their reporting and decision-making processes, companies can enhance their

sustainability efforts, strengthen stakeholder relationships, and drive

positive impact on both financial and non-financial fronts.

Materiality in Different Frameworks

Different sustainability reporting frameworks offer varying

approaches to defining and addressing materiality:

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI): GRI adopts a broad view of materiality, considering not only financial impacts but also the organization’s influence on the environment, society, and the economy. GRI encourages organizations to focus on a wide range of issues that are important to various stakeholders, making it ideal for comprehensive sustainability reporting.

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB): SASB narrows the focus to financially material issues—those that are most likely to affect a company’s financial performance. SASB standards are industry-specific, allowing companies to concentrate on the ESG issues most relevant to their sector.

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): TCFD emphasizes materiality in the context of climate-related risks and opportunities. It focuses on how climate change impacts an organization’s financial health, urging companies to consider climate-related issues in their governance, strategy, and risk management processes.

Each framework’s approach to materiality influences the

scope and depth of reporting, and companies should choose the framework that

best aligns with their reporting objectives and stakeholder needs.

Scope:

Defining the Boundaries of Your Report

The scope of sustainability reporting defines the boundaries

of the reporting process. It determines what activities, operations, and

impacts are included in the report. The scope should be aligned with the

organization's materiality assessment, ensuring that the report covers the most

significant issues. Scope can be viewed

from two perspectives: the scope of reporting boundaries, which defines what

parts of the organization and its activities are included in the report, and

the scope of data collection, which outlines the specific types of data that

are measured and reported.

Several factors influence the scope of sustainability

reporting:

- Industry: Different industries have different sustainability challenges and priorities. For example, a manufacturing company might focus on energy efficiency and emissions, while a retail company might prioritize ethical sourcing and labor practices.

- Business Model: The organization's business model and operations will also impact the scope of reporting. A company with a global supply chain will need to consider the sustainability impacts across its entire value chain.

- Stakeholder Expectations: The expectations of key stakeholders, such as investors, customers, and employees, should be considered when determining the scope of reporting.

Scope of

Reporting Boundaries

When setting the scope of reporting boundaries,

organizations must decide which entities, operations, and value chain

activities will be included in their sustainability report. This involves

determining whether the report will cover just the parent company, all

subsidiaries, or certain segments of the value chain, such as suppliers and

distributors.

Key Considerations for Defining Scope

- Materiality: The scope should be aligned with your materiality assessment. This means that your report should cover the most significant sustainability issues that impact your organization's financial performance, operations, and reputation.

- Value Chain: Consider the entire value chain of your organization, from raw material sourcing to product manufacturing, distribution, and end-of-life management. Include all relevant activities and impacts within the scope of your report.

- Geographical Footprint: If your organization operates in multiple locations, determine the geographical scope of your report. Do you want to report on all operations globally, or focus on specific regions or countries? Or product line-specific or project specific?

- Timeframe: Specify the timeframe for your report. Are you reporting on a single year, a multi-year period, or a specific project or initiative?

- Stakeholder Expectations: Consider the expectations of your key stakeholders, such as investors, customers, employees, and communities. What information are they looking for?

Organizational Boundaries

- Operational Control Approach: Companies report on all activities over which they have operational control, regardless of ownership. This approach often aligns with how companies manage their operations and implement policies.

- Equity Share Approach: Companies report based on their share of equity in each entity, reflecting their financial ownership in various operations. This approach aligns closely with financial reporting.

- Financial Control Approach: Companies report on entities and operations that they financially control, typically those consolidated in financial statements.

Value Chain Boundaries

Companies must decide whether to include only direct

operations (upstream and downstream) or to extend their reporting to include

suppliers, distributors, and even customers. This is particularly relevant in

industries with significant environmental or social impacts throughout the

supply chain.

For example, a company might choose to report only on its

manufacturing operations, or it might extend its scope to include the sourcing

of raw materials and the disposal of products at the end of their lifecycle.

The choice of boundaries affects the completeness and credibility of the

sustainability report.

Tips for

Defining Scope

- Be Clear and Concise: Clearly define the scope of your report in the introduction or executive summary.

- Use Consistent Terminology: Use consistent language and definitions throughout the report.

- Provide Context: Explain the rationale behind your scope choices and the criteria used for inclusion and exclusion.

- Be Transparent: Disclose any limitations or exclusions in your scope.

Benefits

of a Well-Defined Scope

- Improved Focus and Relevance: A clear scope helps ensure that your report is focused on the most important issues and relevant to your stakeholders.

- Enhanced Credibility and Transparency: A well-defined scope enhances the credibility and transparency of your report by clearly outlining the boundaries of your reporting process.

- Increased Efficiency and Effectiveness: A focused scope allows you to allocate resources more effectively and concentrate on the most impactful sustainability initiatives.

Scope of

Data Collection

Scope 1 Emissions:

These are direct GHG emissions from sources that are owned

or controlled by the organization. This includes emissions from on-site energy

generation, company-owned vehicles, and industrial processes. For instance, a

manufacturing company would report emissions from its factories and company

vehicles under Scope 1.

Scope 2 Emissions:

These are indirect GHG emissions from the generation of

purchased electricity, steam, heating, and cooling consumed by the

organization. Although these emissions occur at the power plant, they are a

result of the organization’s energy consumption. Companies that rely heavily on

purchased electricity, such as those in the tech industry with large data

centers, would report significant Scope 2 emissions.

Scope 3 Emissions:

These are all other indirect emissions that occur in the

company’s value chain, including both upstream and downstream emissions. This

could involve emissions from the production of purchased goods and services,

transportation, business travel, and even the end-use of sold products. Scope 3

emissions are often the largest component of a company’s carbon footprint, but

they are also the most challenging to measure accurately.

Data collection for sustainability reporting goes beyond

emissions to include metrics on water usage, waste generation, labor practices,

and community impacts. The comprehensiveness of the data collection process

depends on the defined scope and the materiality of different issues to the

organization and its stakeholders.

For instance, a company with a significant environmental

impact may focus on detailed reporting of emissions and resource use, while a

service-based organization might prioritize social data, such as employee

well-being and customer privacy.

Integrating

Materiality and Scope in Sustainability Reporting

Coherence Between Materiality and Scope

The first step in aligning materiality and scope is to

ensure that the material issues identified are adequately covered within the

defined scope of the report. For example, if reducing carbon emissions is

identified as a material issue, the scope should include all operations,

processes, and parts of the value chain that contribute significantly to the

organization’s carbon footprint.

Companies must also consider the breadth of their scope in

relation to materiality. A narrowly defined scope might overlook important

issues, leading to a report that fails to capture the full extent of the

organization’s sustainability impacts. Conversely, an overly broad scope might

dilute the focus on material issues, making the report less useful for

stakeholders.

Incorporating Stakeholder Perspectives

Integrating materiality and scope requires ongoing dialogue

with stakeholders. Stakeholders can provide valuable insights into which issues

are material and how the scope should be defined to address these issues

effectively. Engaging stakeholders ensures that the report aligns with their

expectations and meets the information needs of investors, customers,

employees, and other interested parties.

Regular stakeholder engagement also helps organizations stay

responsive to changing priorities. As new material issues emerge, the scope may

need to be adjusted to capture these developments accurately.

Dynamic Integration

The integration of materiality and scope is not a one-time

task but a dynamic process. As an organization’s operations evolve and

stakeholder expectations shift, both materiality and scope should be revisited

and refined. This may involve expanding the scope to include new areas of

impact or narrowing it to focus more intensely on key material issues.

Companies should establish a process for regularly reviewing

and updating their materiality assessments and scope definitions. This ensures

that the sustainability report remains relevant and continues to provide

stakeholders with the information they need to make informed decisions.

Case Studies or Examples

Understanding how other companies have successfully integrated materiality and scope into their sustainability reporting can provide valuable insights and practical examples to follow. Below are a few illustrative examples:

Example 1: A Global Retailer:

A large retail company identified supply chain labor

practices as a material issue due to stakeholder concerns about ethical

sourcing. To address this, the company expanded its reporting scope to include

its entire supply chain, from raw material sourcing to finished product

delivery. This integration allowed the company to provide a comprehensive view

of its efforts to ensure fair labor practices throughout its value chain,

aligning with its materiality focus on social responsibility.

Example 2: A Manufacturing Firm:

A manufacturing company focused on reducing its

environmental impact identified energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions

as material issues. To align scope with materiality, the company included all

facilities, transportation logistics, and even downstream emissions from

product use in its reporting scope. This approach provided stakeholders with a

clear understanding of the company’s total environmental impact and its efforts

to mitigate these effects across all relevant areas.

Example 3: A Financial Institution:

A financial institution recognized climate-related financial

risks as a material issue due to regulatory pressures and investor interest.

The institution’s reporting scope was aligned to include all operations and

investments, with a particular focus on assessing the carbon footprint of its

loan and investment portfolios. This integration allowed the institution to

report comprehensively on how it is managing climate-related risks in line with

the expectations of both regulators and investors.

Best Practices for Integrating Materiality and Scope

To achieve effective integration of materiality and scope in

sustainability reporting, companies should consider the following best

practices:

Regular Updates and Reassessment

Continuously review and update the materiality assessment

and scope definitions to reflect changes in the business environment,

regulatory landscape, and stakeholder priorities.

Incorporate new data and insights from ongoing stakeholder

engagement to refine the report’s focus and boundaries.

Cross-Functional Collaboration

Engage cross-functional teams within the organization to

ensure that both materiality and scope are accurately defined and aligned with

overall business strategy. Collaboration between sustainability teams, finance,

operations, and risk management ensures that all relevant issues are

considered.

Clear Communication

Transparently communicate how materiality and scope have

been integrated in the sustainability report. This includes explaining the

criteria used to define material issues, the boundaries of the reporting scope,

and any changes from previous reporting periods.

By thoughtfully integrating materiality and scope,

organizations can create sustainability reports that are both relevant and

credible, providing stakeholders with the insights they need to understand the

company’s true impact and performance.

Defining

Materiality and Scope: A Practical Approach

Determining materiality involves a systematic process of

identifying, evaluating, and prioritizing issues that have a significant impact

on the organization and its stakeholders. This process typically begins with

stakeholder engagement, where companies gather input from investors, customers,

employees, regulators, and the community. Engaging stakeholders ensures that

the issues considered material truly reflect the concerns and interests of

those affected by the company’s operations.

Tools like materiality matrices are often used to visually

represent and prioritize these issues based on their significance to

stakeholders and their impact on the business. By mapping out these issues,

companies can focus their reporting on the most critical areas, ensuring that

their sustainability reports are relevant, concise, and impactful.

Here's a practical approach to defining materiality and

scope:

1. Identify Material Issues

- Conduct a Materiality Assessment: Begin by conducting a comprehensive materiality assessment to identify the sustainability issues that are most relevant to your organization's financial performance, operations, and reputation. This assessment should consider both internal and external factors.

- Internal Analysis: Analyze your organization's operations, value chain, and strategic goals to identify potential sustainability impacts. Consider factors such as resource consumption, emissions, waste generation, labor practices, community relations, and supply chain management.

- External Analysis: Research industry trends, regulatory requirements, stakeholder expectations, and emerging sustainability issues to understand the broader context of your operations. Refer to industry-specific guidelines, sustainability frameworks (GRI, SASB, TCFD), and relevant reports from other companies in your sector.

- Data Collection: Gather data related to your organization's sustainability performance, including environmental impact, social initiatives, and governance practices. This data will help you assess the significance of different sustainability issues.

- Define Boundaries: Once you've identified material issues, define the boundaries of your sustainability report. This involves determining the geographical scope (global, regional, or specific locations), the time frame (single year, multi-year period, or specific project), and the activities or operations included in the report.

- Value Chain Analysis: Consider your organization's entire value chain, from raw material sourcing to product manufacturing, distribution, and end-of-life management. Determine which parts of the value chain are most relevant to your material sustainability issues and include them in the scope of your report.

- Stakeholder Expectations: Engage with stakeholders to understand their priorities and expectations regarding sustainability reporting. Consider the information they need to make informed decisions about your organization.

3. Engage Stakeholders

- Collaborative Approach: Engage stakeholders throughout the process of defining materiality and scope. This ensures that the report is relevant to their needs and reflects their priorities.

- Stakeholder Workshops: Conduct workshops or meetings with stakeholders to discuss material issues, gather feedback, and reach consensus on the scope of reporting.

- Surveys and Feedback Mechanisms: Use surveys and online platforms to collect feedback from a broader range of stakeholders, including customers, investors, employees, and community members.

- Transparency and Communication: Communicate clearly and transparently with stakeholders about the process of defining materiality and scope, the rationale behind your decisions, and the limitations of your report.

4. Tools and Techniques

- Materiality Matrix: Use a materiality matrix to visually represent the significance of different sustainability issues based on their impact on your organization and stakeholder concerns.

- Stakeholder Mapping: Create a stakeholder map to identify key stakeholder groups, their interests, and their influence on your organization.

- Risk Assessment: Conduct a risk assessment to identify potential risks and opportunities associated with sustainability issues. This helps prioritize issues based on their likelihood of occurrence and potential impact.

- Data Analytics: Use data analytics tools to analyze sustainability data and identify trends, patterns, and areas for improvement.

5. Communicate Effectively

- Clear and Concise Language: Use clear and concise language in your sustainability report to communicate materiality and scope effectively to stakeholders.

- Contextual Information: Provide context for your sustainability disclosures, explaining the rationale behind your decisions and the criteria used for inclusion and exclusion.

- Visual Representations: Use charts, graphs, and tables to present data and information in a visually appealing and easy-to-understand manner.

- Transparency and Disclosure: Be transparent about any limitations or exclusions in your scope and disclose any data limitations or uncertainties.

6. Continuous Improvement

- Regular Review: Regularly review your materiality assessment and scope to ensure they remain relevant and aligned with evolving stakeholder expectations, industry trends, and organizational priorities.

- Feedback Mechanism: Establish a feedback mechanism to gather feedback from stakeholders on your sustainability reporting. This helps you identify areas for improvement and ensure that your reports are meeting their needs.

- By following this practical approach, organizations can effectively define materiality and scope, creating sustainability reports that are focused, relevant, and impactful. This process fosters transparency, builds trust with stakeholders, and helps organizations drive positive change through their sustainability initiatives.

Conclusion

Understanding and effectively integrating materiality and

scope in sustainability reporting is essential for organizations aiming to

create impactful and credible reports. As companies navigate the complexities

of defining what is material and determining the appropriate scope, they must

balance a range of considerations, from stakeholder expectations to data

collection challenges and competitive sensitivities.

By adopting best practices, engaging stakeholders,

leveraging technology, and staying adaptable to evolving circumstances,

companies can overcome these challenges and produce sustainability reports that

are not only comprehensive but also truly reflective of their environmental,

social, and governance impacts.

Ultimately, a well-crafted sustainability report does more

than just meet regulatory requirements; it serves as a powerful tool for

building trust, enhancing transparency, and driving long-term value for both

the organization and its stakeholders. As the landscape of sustainability

continues to evolve, companies that are proactive in refining their materiality

assessments and scope definitions will be better positioned to lead the way in

responsible business practices and sustainable growth.

Comments

Post a Comment