Understanding ISSB S1 and S2: The New Global Standards for Sustainability Reporting

The Push for Global Sustainability Transparency

In today’s corporate landscape, sustainability is no longer

just a buzzword—it’s a critical driver of business resilience and investor

confidence. However, for years, companies faced a major challenge: the lack of

a unified system for reporting environmental, social, and governance (ESG)

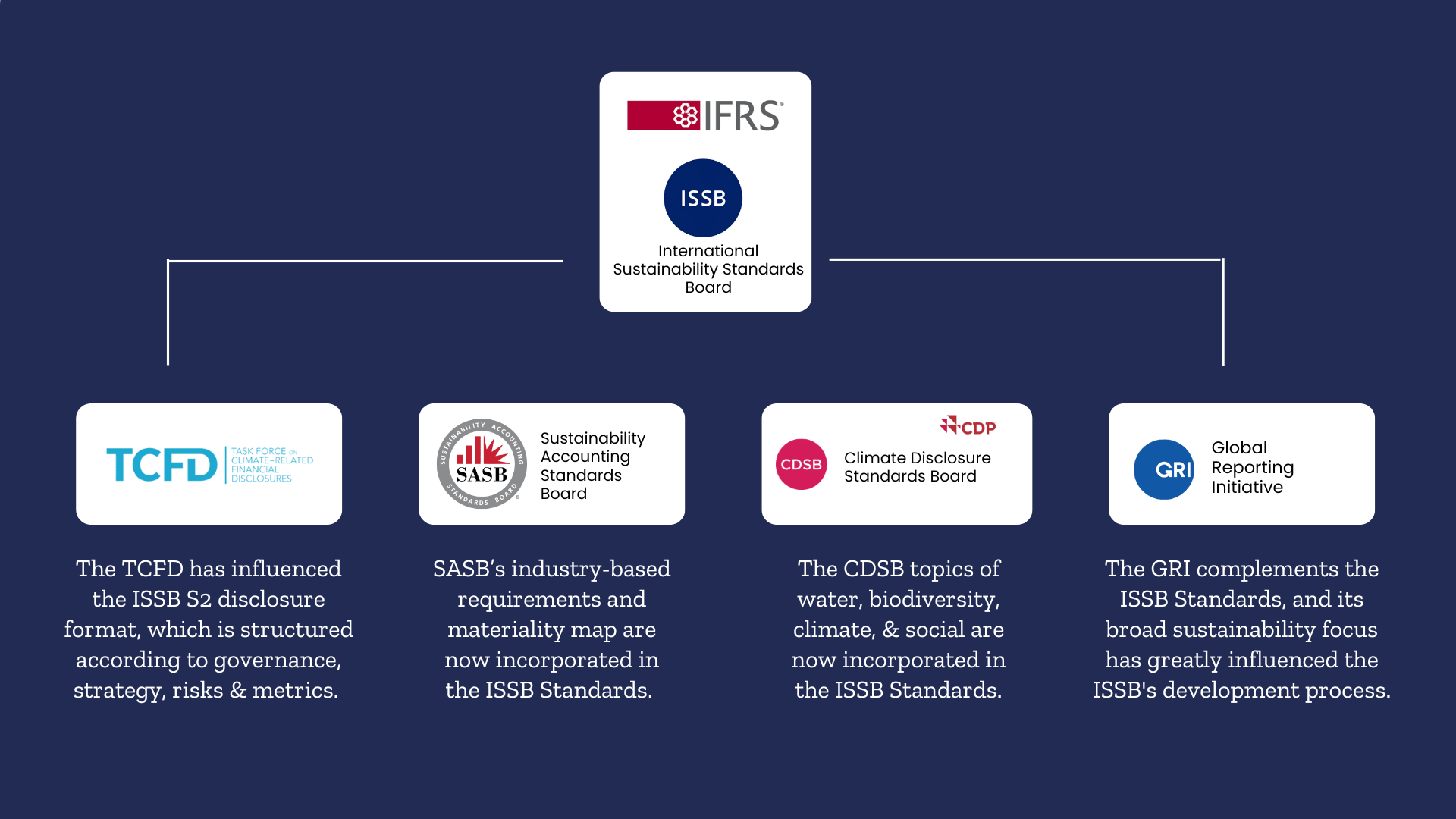

risks. With dozens of competing frameworks—from GRI and SASB to TCFD—investors

struggled to compare data, while businesses wasted resources navigating

inconsistent requirements.

This changed in 2021 when the IFRS Foundation, the

organization behind the widely adopted International Financial Reporting

Standards (IFRS), established the International Sustainability

Standards Board (ISSB). Its mission? To create a global baseline for

sustainability disclosures, mirroring the clarity that IFRS brought to

financial accounting.

In June 2023, the ISSB delivered its first two

standards: IFRS S1 (general sustainability disclosures)

and IFRS S2 (climate-specific reporting). Together, they mark

a turning point in corporate transparency. This article explains their

background, key requirements, and why they matter for businesses and investors

alike.

The Origins of ISSB: Filling the Sustainability Reporting Gap

Before diving into S1 and S2, it’s essential to understand

the problem they solve. Historically, sustainability reporting was fragmented.

A company might use the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to

discuss its social impact, the Sustainability Accounting Standards

Board (SASB) for industry-specific risks, and the Task Force

on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) for climate scenarios.

This patchwork made it difficult to assess performance across companies or

sectors.

Meanwhile, investors demanded better data. A 2023 CFA Institute survey found that 85% of investment professionals consider sustainability disclosures material to their decisions. Regulators also stepped in, with the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the U.S. SEC’s proposed climate rules adding pressure for standardized disclosures.

The IFRS Foundation responded by launching the ISSB in 2021,

tasking it with developing a global lingua franca for

sustainability reporting—one that prioritizes decision-useful, financially

material information.

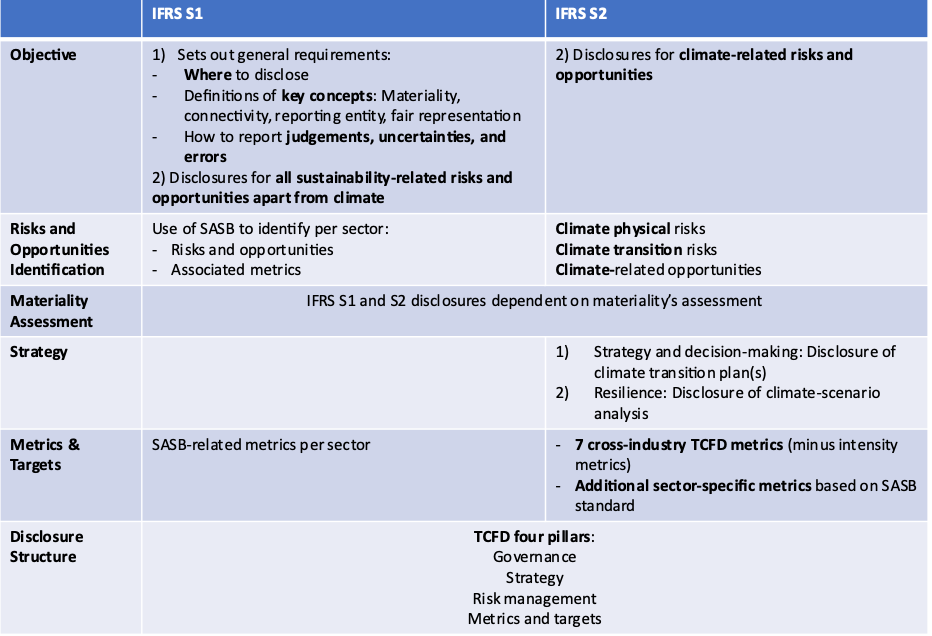

IFRS S1: The Foundation for Sustainability Disclosures

IFRS S1 provides the overarching framework for how companies should report sustainability-related risks and opportunities. Unlike broad ESG frameworks, S1 focuses specifically on financially material issues—those that could influence cash flows, access to capital, or long-term resilience. Think of it as the "core rulebook" that ensures disclosures are comparable and relevant to investors.

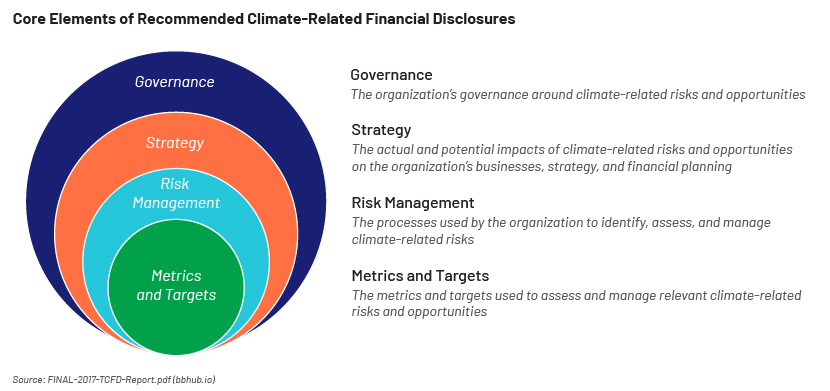

Under S1, companies must address four key areas:

- Governance:

How boards and management oversee sustainability risks. For example, Nestlé’s

2023 report outlines how its Board’s Corporate Governance

Committee reviews climate risks quarterly, with CEO bonuses linked to

plastic reduction goals. This aligns with S1’s governance rules. Poor governance of sustainability risks

can lead to crises. Volkswagen’s "Dieselgate" scandal (2015)

showed how weak oversight of environmental compliance resulted in €30B+ in

fines—a risk S1 aims to mitigate. Key

Requirements includes:

- Board-level

accountability: Describe the governance body (e.g., a sustainability

committee) responsible for oversight.

- Management’s role:

Explain how executives integrate sustainability into business strategy

and risk management.

- Incentive alignment: Disclose if executive compensation is tied to sustainability targets (e.g., carbon reduction).

- Strategy:

The actual and potential impacts of sustainability issues on business

models and financial planning. Siemens uses

S1-aligned reporting to show how its shift to renewable energy services

(like grid modernization) could generate €50B in revenue by 2030,

offsetting declines in fossil fuel-related sales. Ignoring risk planning

can result in having negative financial impact like BP’s $17.5B write-down

of oil assets in 2020 due to their delayed transition planning. Key Requirements include:

- Short-, medium-, and

long-term effects: For example, how water scarcity could disrupt

manufacturing by 2030.

- Scenario analysis:

Use plausible future scenarios (e.g., 2°C warming) to assess financial

impacts.

- Competitive

positioning: How sustainability creates opportunities (e.g., Tesla’s

EV market dominance amid fuel regulations).

- Risk

Management: Processes to identify, assess, and mitigate sustainability

risks. Coca-Cola’s reports its

water-stress risk assessments in drought-prone regions, with $2B

invested in water efficiency since 2010—a direct response to a

financially material risk. Key requirements

include:

- Risk identification: Tools used (e.g., materiality assessments, stakeholder engagement).

- Integration with ERM: How sustainability risks are embedded into enterprise-wide risk management.

- Mitigation actions: Policies, due diligence, and investments to reduce risks (e.g., Apple’s $4.7B Green Bond for carbon-neutral supply chains).

- Metrics

and Targets: Quantitative data (e.g., carbon emissions, water usage)

and progress toward goals. For example,

IKEA’s "Climate Positivity" plan tracks 1,500+

metrics, from renewable energy use (%) to supply chain emissions per product

that is all verified by third parties.

Failure to include targets or disclosing vague targets can erode

trust. For example, when Amazon’s

"Climate Pledge" failed to disclose Scope 3 emissions (2021),

critics accused it of greenwashing—a pitfall S1’s metrics rules address.

Crucially, S1 adopts a financial materiality lens—focusing

on sustainability factors that could reasonably affect a company’s cash flows

or access to capital. This distinguishes it from broader impact-focused

frameworks like GRI.

How the Four Pillars of IFRS S1 Work Together: A Dynamic Feedback Loop

At first glance, IFRS S1’s four pillars—Governance,

Strategy, Risk Management, and Metrics & Targets—might appear as

standalone requirements. But in practice, they function as an interconnected

system, where each element informs and reinforces the others. This creates a

continuous feedback loop that helps companies not just report on

sustainability, but actively manage it as a core driver of financial

resilience. Here’s how it flows in

practice:

- Governance

sets the tone: When Siemens tied executive pay to decarbonization, it

signaled sustainability was a priority, not just optics.

- Strategy

translates priorities into action: Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan

identified plant-based foods as a growth opportunity, anticipating

consumer and regulatory shifts.

- Risk

Management operationalizes strategy: Nestlé invests in water-saving

tech at high-risk factories, turning strategic plans into tangible

safeguards.

- Metrics

close the loop: Microsoft’s annual carbon tracking allows course

corrections, like reallocating investments when suppliers miss targets.

The Power of the Cycle

Ørsted’s energy transition shows this in action. Governance committed to

renewables, strategy pivoted to wind power, risk management phased out coal

early, and metrics confirmed the approach worked—accelerating further

investment. Firms like Ørsted that treat

these pillars as interconnected see fewer surprises (MSCI found 25% lower

earnings volatility). Those that don’t, like Boeing with its 737 MAX, face

preventable crises. In short, S1’s

framework turns sustainability from a reporting task into a strategic

advantage—when all parts work together.

IFRS S2: Climate-Specific Reporting

While S1 covers all sustainability topics, IFRS S2 zeroes in on climate change—the most urgent and systemic risk facing businesses today. S2 requires companies to disclose how climate risks and opportunities impact their bottom line, going beyond generic sustainability statements to provide investors with decision-useful data.

S2 requires detailed disclosures on:

- Climate-related

risks and opportunities, including physical risks (e.g., floods) and

transition risks (e.g., policy shifts). Physical risks can be like costs

from increasing wildfires (e.g., PG&E’s $25B wildfire liabilities),

floods, or supply chain disruptions. Beverage giants like Coca-Cola now

quantify how water scarcity in key regions could raise production costs by

15-20% by 2030.

- Transition

plans: How the company is preparing for a net-zero economy, including

investments in clean energy or efficiency.

Automakers like Ford disclose how stricter EU emissions rules could

dent ICE vehicle sales while boosting EV demand. Investors need to see both sides.

When Shell downgraded its 2030 renewable energy targets in 2024,

its shares fell 5%—showing how transition missteps hit valuations.

- Greenhouse

gas emissions: Scopes 1, 2, and 3 emissions, with Scope 3 (indirect

emissions) being a major focus for many industries. Most firms lack Scope 3

visibility. Amazon’s early resistance to disclosing it (2021)

drew activist pressure. Now, its Climate Pledge Fund requires suppliers to

share emissions data—a shift S2 will standardize.

- Climate

resilience: Scenario analyses showing how the business might perform

under different warming pathways. Agricultural

firms like Cargill assess crop yield drops under drought scenarios.

Notably, S2 fully incorporates the TCFD

recommendations, streamlining reporting for companies already using this

framework.

Once again, these pillars aren’t standalone—they’re

interconnected:

- Risks

inform transition plans (e.g., Coca-Cola’s water risks → $2B

efficiency investments).

- Emissions

data validates plans (Microsoft’s Scope 3 tracking ensures its

$1B/year fund hits targets).

- Resilience

tests reveal gaps (Swiss Re’s 3°C scenario showed reinsurance

gaps, prompting new products).

Why These Standards Matter

The ISSB standards address three critical gaps in

sustainability reporting:

By replacing a maze of frameworks with a single baseline, S1 and S2 enable investors to compare companies’ sustainability performance as easily as they compare financial statements. A 2022 study by the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) found that 80% of institutional investors discard ESG reports due to inconsistent metrics, making ISSB’s standardization a game-changer. Research by Harvard Business School (2023) showed companies with strong sustainability disclosures had lower capital costs by up to 1.5%, as investors perceived them as lower-risk.

Efficiency for Businesses

Companies can now focus on one set of global standards rather than juggling multiple reporting requirements. This is especially valuable for multinational firms operating in different regulatory jurisdictions. A KPMG survey (2023) found that 70% of multinationals use at least three different ESG frameworks, costing an average of $700,000 annually in compliance overhead. ISSB’s global baseline could slash these costs.

Credibility for Stakeholders

With stringent data requirements and a focus on financial materiality, ISSB helps curb greenwashing by tying sustainability claims to measurable outcomes. A 2023 European Central Bank study found that 42% of "sustainable" funds mislabeled their ESG claims—a problem ISSB’s auditable metrics aim to fix. When H&M was accused of greenwashing in 2022, its lack of standardized disclosures (now required under ISSB S1’s governance and metrics rules) exacerbated reputational damage. Post-scandal, it adopted stricter reporting, aligning with ISSB prototypes.

Financial Performance and Climate Risk Links

A 2024 MSCI analysis of 9,000 companies revealed those failing to disclose climate risks (per ISSB S2) had 18% higher volatility in earnings calls. For example, after Unilever implemented TCFD-style reporting (now ISSB S2), it identified €300 million in cost savings from energy efficiency—data it previously didn’t track systematically.

The ISSB standards aren’t meant to replace existing

frameworks but to complement them. For example:

- GRI remains

relevant for organizations wanting to report on their societal impact.

- SASB’s industry-specific

metrics are now integrated into ISSB.

- EU’s

CSRD goes beyond financial materiality but aligns with ISSB on

many climate disclosures.

This "interoperability" ensures companies can layer ISSB onto their current reporting practices without starting from scratch.

What’s Next?

With jurisdictions like the UK, Japan, and Canada moving to

adopt ISSB-aligned reporting, companies should start preparing now. Early

adopters will not only meet regulatory demands but also gain a competitive edge

in attracting capital and talent.

In our next post, we’ll provide a step-by-step guide to

implementing ISSB S1 and S2, including how to gather data, structure

disclosures, and avoid common pitfalls.

For businesses, the message is clear: The era of

inconsistent sustainability reporting is ending. Those who adapt early will

lead the transition to a more transparent—and sustainable—future.

Comments

Post a Comment